HCI Review of the Xerox Star

The Contributions and the Downfall of the Xerox Star

The Beginning

In 1979 at the Office Products Division in Dallas, Don Massaro took a gamble and pushed to market the Xerox 8010, a.k.a. "Star". He was very impressed with the incredible technology that Star had. It was back in 1976 under the Software Development Division of Xerox that the idea of Star began to take shape. The Star displayed such technologies as bitmapped screens, windows, a mouse-driven interface, and icons that distinguished it from other systems. The Star and its predecessor, the Alto, influenced people such as Steve Jobs of Apple (who would soon release the Apple Lisa and its more successful descendant the Apple Macintosh).

The technologies that make up the Star extend as far back as 1945. A man by the name of Dr. Vannevar Bush printed an article in the July 1945 issue of The Atlantic Monthly entitled "As We May Think". In the article, he offers military scientists a different role once the fighting ceased. The role of making our store of knowledge more accessible. The article envisions instruments that when properly developed, will give man access and command over knowledge. Dr. Bush foresaw a computer designed for the purposes of applications other then number manipulation. He called it the Memex. However, the technology and the imagination needed to implement it were not there at the time.

In the 1960s, Ivan Sutherland (now of Sun Microsystems) developed Sketchpad as an interactive graphics system. It allowed users to create graphics on the screen with a light pen. The graphics were treated as objects to be manipulated. These object could be joined together to form more complex objects which then can be treated as units. This became the influence for Star's user interface and graphical applications.

During the 1960s, Douglas Engelbart and his colleagues created the On-Line System (NLS) that was implemented with what was to be called hypertext. NLS provided key tools such as teleconferencing, e-mail, word processing, hypertext linking, idea development editors and user controlled configuration and programming. However, in order for the NLS to work, tools had to be developed. Among these were the mouse, a chord keyboard, a full windowing software environment, on-line help and consistency of the user interface. The Star development team became inspired by the use of textual and graphical information in trees and networks. One of these members was Rich Pasco who came to Atari in 1983 to try to convince them to place a mouse on the Atari 800. He even had an interface and drivers prepared.

Another chief influence of the Star was Alan Kay. He wrote a paper about the Reactive Engine concept. He also developed the Smalltalk language.

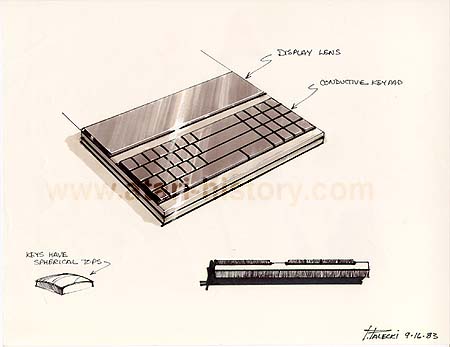

Kay used the Alto to build his version of a personal computing system that would supply users with the building blocks needed to make tools and applications for individually defined information processing problems. He developed prototypes for a laptop computer, called Dynabook. As with Dr. Bush, the technology for this laptop system was unavailable at the time.

The prototypes developed in Xerox eventually evolved into the Smalltalk language, with the help of children. Kay had concluded that children learn more from sounds and graphics rather then text. So Smalltalk relied heavily on graphics and animation. Even though Smalltalk promoted bitmapped displays, mouse input, windowing environment and simultaneous applications, Star was not written in Smalltalk, as many people would like to believe.

Kay worked with Xerox from 1972 but some of his most revolutionary ideas didn't get the funding that he had hoped for. He left Xerox in 1983 and briefly worked for Atari as chief scientist and headed up many R&D projects. The conceptual designs of Alan Kay's Databook, as Dynabook was now called, met Alan's specifications exactly.

II. From www.atari-history.com

III: From www.the-dock.com/club100

Xerox PARC.

Before the Xerox acquired Scientific Data Systems, a researcher was hired. The researcher recommended that Xerox should create a technology center for researching digital technologies. It was thought that analog technologies were inadequate for the future and that the copier industry would be vulnerable. The idea was to combine copier and digital technologies within integrated office systems. Thus in 1970, the Palo Alto Research Center, or PARC was born."The best way to predict the future is to invent it."

--Alan Kay

Alan Kay happened to have been one of the founding members of PARC. He along with his colleagues became aquatinted with the NLS and was impressed with what they saw. Members from the NLS were hired and two things happened. The mouse was licensed to Xerox in 1971 and the term "personal computer" was coined in 1973. Kay and his team created a vision of a distributed environment populated with personal computers. The Xerox Alto was a product of this vision. Four important events took place:

Although later versions of the Alto proved to be disastrous, it paved the way for Star. One of the developers was David C. Smith, who wrote the first large program in Smalltalk. He introduced the concept of using images that users can manipulate that acts on the represented data. The images are known now as icons. Two other developers, Charles Simonyi and Butler Lampson contributed a document editing system called Bravo which demonstrated the WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) concept to its fullest extent at the time. The text could be edited on-screen with such features as boldface, italics, and underline, with the exact same image shown on laser printer. Bravo was used throughout Xerox. Larry Tesler's prototype text editor, Gypsy, among other prototypes and ideas were adopted into Bravo and BravoX was later released. The developers of BravoX left to different companies that resulted in the release of Microsoft Word and LisaWrite. Both products are direct descendants of BravoX. Laurel and Hardy are E-mail packages that allowed E-mail to become more accessible to the non-engineering staff at Xerox and eventually became crucial to Star. Finally, OfficeTalk, written by Clarence Ellis and Gary Nutt, demonstrated common office tasks and jobs as they go from person to person within an organization. As developers became more experienced with OfficeTalk, they gained ideas for Star, since both systems had common goals.

Stars graphical capabilities came from such products as Draw and Sil, which succeeded Sutherland's Sketchpad. Markup, a bitmap editor (or a paint program) and Flyer, another paint program written in Smalltalk were both written for the Alto which inspired Doodle. Doodle evolved into Free-Hand Drawing for ViewPoint (a descendant of Star). The laser printer, invented at PARC, was invented to match the quality of the text and graphics from the screen to paper. Press (later developed into Interpress) became a page-description language in which any computer can describe what the output is going to be to the laser printer. This became a part of the Star system. Some developers of Press and Interpress later formed Adobe and developed a more modern page-description language, Postscript.

When Xerox PARC was developing the first GUI, as seen on the 8010, Lee Jay Lorenzen was a key member of the team. He was later hired by Digital Research Inc., where he worked on a GUI he wanted to call Crystal (after an IBM project at the time, called Glass). Since Crystal was already trademarked, the project was renamed Gem. The acronym GEM (Graphical Environment Manager) came later. Lee wrote the vast majority of GEM/1 following his designs from the Xerox closely. In fact, his expertise writing first the Xerox system and later GEM allowed him to walk away from DRI and create a smaller cut-down version for his company, Ventura. An exchange happened between DRI and Gary Kildall at the Atari Grass Valley research center. Gary was given a VAX 11/750 in exchange for the development of CP/M 68K and GEM, which became TOS for the Atari ST line. GEM was also developed for early DOS computers. In fact, Elixir Desktop was built on top of the final version of GEM, version 3.

The Birth of Star

Under the Systems Development Department, which had been already established, the Star project had been underway under a different codename, "Janus". The original plan was to "look forward to office information systems and backward to word processing". After a conference in late 1977 and for security reasons, the codename was changed to "Star" and the development went under way. The group in Palo Alto worked on the operating system and programming language of the Star while the El Segundo group designed the user applications. The original processor for Star had to be changed because of the complexity involved and the expenses needed to power it. The Star also set an odd precedent where the software was developed before the hardware. Nevertheless, the Star system under the support of Don Massaro continued on.

Star actually refers to the software that was to be used in conjunction of the machine developed by Xerox and not the machine itself, although it's easy to see the misunderstanding. Chuck Thacker along with the help of Butler Lampson were faced with the task of developing a processor to run the object code produced from the Palo Alto group (the language now known as MESA). Microprograms were included to handle low-level display operations. It was decided that the complete Star package should include:

The effort that went into designing the Star was phenomenal. A strict format had to be followed and designers were forced to think clearly about the application development. The Ethernet helped with the developing process since the staff at Palo Alto and at El Segundo needed constant communication with each other. Massaro now believed that the Star would either be on the verge of success or failure. With the impressive new technologies of Star and the software included, Massaro was convinced enough that David Liddle (then head of the SDD), didn't need to go through the entire demonstration. Alas, Star fell short on a number of expectations that led to the development of ViewPoint, Don Massaro's resignation and an increasing jealousy in the photocopier division of Xerox.

The Limitations and the Fall of Star

The Hardware Limitations

The software developed for the Star was designed for the user who has no computer knowledge became very demanding on the hardware. There was no chance of the Star running at a reasonable speed due to memory consumption and the number of hardware cycles needed. The Star suffered from being a distributed personal computer and not a personal computer like the then released IBM PC. This was the result of Xerox secluding itself from the demands of the marketplace. Staff at SDD were so concerned about making the perfect system that they used more innovation then necessary. No constraints were placed on the engineers. In contrast, the IBM PC had the advantage of being scaled down for both users and developers alike. The Star was designed for distributed computing, requiring such components as laser printers, networked computers, and electronic filing cabinets. The IBM PC, on the other hand worked well on its own, or with a lesser quality printer, and proved to be a cheaper alternative.

The developers for Star assumed that the software developed for the user would be the only software they needed, thus becoming a closed system. Having the software developed before the hardware also became a problem. Thus, the Star became a multitasking system that couldn't multitask as well as hoped.

The Software Limitations

A major downfall of the Star software was the fact that it was designed to the developers view of what the user needs. As a result, spreadsheet software that can run on other computer systems had no hope of running on Star. Since Star targeted managers and executives, the mistake was not a good one. The developers were never counseled on what executives and managers needed because hardly anyone else at Xerox was interested enough in Star.

No other company could develop software for the system because the programming language was never publicly released. Oddly enough, the "software lock-in" was a strategy that IBM had used in the past, a strategy that the SDD wanted to duplicate. Another part of the demise of Star was the fact that it was ahead of its time and no one really understood the full potential of the software outside of the PARC developers.

The Organizational Downfall

The main handicap of Star probably wasn't as much technical as it was organizational. Each of the technical problems could have been remedied with more developments. Xerox had created a product that it couldn't sell. The sales department wasn't oriented to computer sales since they were used was to selling copiers and non-programmable word processors. The price of the Star was about five times as much as a personal computer. An executive would have probably thought twice about purchasing a Star and buy a cheaper PC.

The sales group in the Office Products Division knew little about how the Star could improve productivity as their potential customers. A seminar about the Star later proved that that the sales group, as well as some of the developers, didn't entirely understand the broader issues of office task integration.

Lessons Learned

Star could have succeeded as a system had more than one of the following changes had happened. To be aware of what the user needs instead of telling the user what they need, careful observation of the trends and demand in the computer market could have been made. The developers should have been counseled on what the demands are at an office setting. The photocopier division at Xerox could have kept an open mind as to what was going on in PARC. Star may have received better support as a result.

Externally available software packages would have been possible, if MESA had been publically distributed. Another approach would have been to develop the hardware first. That way Star would have been developed in such a way that the machine could handle the software.

The most important improvement that could have been made was better communication among developers. As well, a better trained marketing and sales staff with experience in computer sales could have helped.

Conclusions

The Xerox Star was an incredible piece of technology in its time that displayed a lot of innovative ideas and impressed a good amount of people in the computer industry. Even though innovation is good, too much innovation is partially what caused Star to fail. The other part was the lack of organization and support. Xerox made its mark in the computer industry but it couldnt shake its image as a copier company.

Other companies, notably Atari, Apple and Microsoft, picked up on the ideas and technologies that was pioneered in Star. The computer industry would have been at a great loss had no one claimed interest. The Star was ahead of its time and the vision of the user interface lives on despite of its failure. In the end, Star had given us a glimpse of the future in the computer industry and in human interaction.

A direct descendent of the Star was the Elixir Desktop from Xerox. It was a PC version of the Star written for Xerox by Bruce Damer and his team, which included Ed Regan who was a UI specialist working with Xerox and PARC. Ed helped with the Star look and feel into the Elixir product line. It was able to do a few of the tasks, such as creating document jobs for large printing systems, which Star had failed to do. The Elixir project began in 1985 and was adopted into Windows in the early 1990's. Today Elixir is still in use by many companies and organizations for high end electronic document printing systems. Thus the influence of Star continues on into the future.

Bibliography

All corrections, suggestions and additions should be sent to:

JohnRedant01@yahoo.comJohn Redant. August 2001. On-going Research Project.